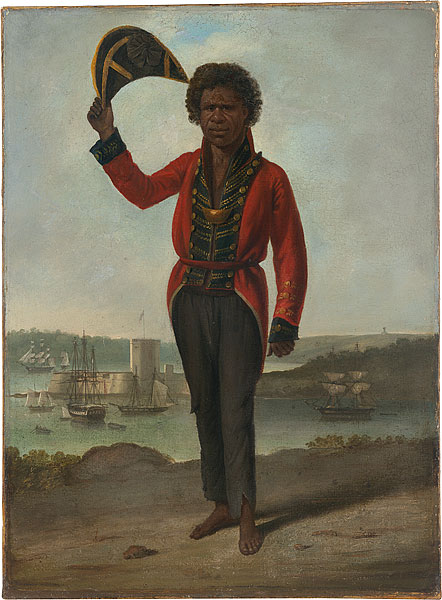

I read a post on LinkedIn about the first major Australian exhibition at The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC. Beauty Rich and Rare was developed over a two year period by The National Library of Australia (NLA) and digital storytellers AGB Events (creators of Sydney’s Vivid festival) and is on show until 5th July 2020. It marks the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s arrival on Australian shores and is an immersive sound and light display featuring original illustrations, charts, and a digital version of Joseph Banks’ journal. The exhibition was shown at the NLA in Canberra concurrently with Cook and the Pacific which examined the legacy of Cook from different angles – “the great navigator, sailor and commander” and from the perspective of the Indigenous people of the Pacific. Cook’s Pacific encounters were a two-way exchange with island nations – nations that had different languages and a unique cultural heritage. Today Cook and the impact of his voyages continues to resonate powerfully across the Pacific.

Recently I’ve undertaken a FutureLearn course (online) called “Confronting Captain Cook: Memorialisation in Museums and Public Places” by the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. The information presented has led me to think more critically about Cook’s voyages and their unresolved impact on the history of the Pacific region (including Australia), and the way in which such historical encounters and Pacific peoples are represented in cultural institutions around the world.

As an Australian, I’d like to know more about the way that Australia is viewed by curators and visitors in museums overseas. The representation of Australia in foreign collections started with Cook and other foreign explorers and the need to gather evidence of “the natural world” and human civilisation (or lack thereof according to European standards) on their voyages. Explorers kept journals and gathered a variety of objects and specimens – both cultural and scientific (including flora, fauna and geological specimens). Curiosities from other lands were collected by institutions in both a “wunderkammer” and scientific sense, without the benefit of context, cultural interpretation or significance to living cultures – without the input which we demand for objects acquired in museums today.

Historic collections should be open to further research, interpretation and rethinking because artefacts are meaningless without specific scientific research or cultural knowledge being attached to them. In particular, Indigenous Australian objects were taken or sourced without Aboriginal voices and meanings, without knowledge of cultural significance and importance attached to them. Some items would still be relevant in 2020 to living Indigenous cultures and should be considered for repatriation rather than remaining stuck in glass cases and conservation stores across the world.

It is shocking to realise that for more than 150 years Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral remains and sacred objects were removed from their communities and placed in museums, universities and private collections overseas. Jennifer Beer from the Aboriginal Heritage Council of Victoria sums it up in these words:

“Secret and sacred objects are a big part of who we are. They carry stories that shape us, and we, and future generations, in turn shape them. They need to be with their rightful custodians so they can keep carrying our stories and our connection with them.”

I want to see Australia’s rich cultural heritage represented in cultural institutions around the world. I’d love to see historic figures, artworks and artefacts given the respect that they deserve on the world stage but honestly this is not occurring in many cultural institutions without appropriate staff, policies and procedures for reviewing historic collections in the contemporary world.

Looking at museum collections online to examine the way Australia is viewed in cultural institutions internationally is an enormous project in itself and would take many years of research. In this post I have sampled a handful of museums presenting Indigenous Australian cultural heritage (tangible and intangible) – one of the oldest in the world dating back 60,000 years.

The National Museum of Australia has published some work on the subject for Australian Museums under Understanding Museums: Australian museums and museology called “Indigenous People and Museums” which speaks critically about indigenous collections, culture and art and repatriation of objects under certain circumstances. Perhaps the information needs a further push to curators and conservators of Indigenous Australian collections in other parts of the world as well as Australia.

Secret or sacred objects include items:

- associated with a traditional burial

- created for ceremonial, religious or burial purposes

- used or seen only by certain people

- sourced from or containing materials that only certain members of the community can use or see

There are some brilliant offerings and interpretation in Australian museums and galleries and there are a number of articles and guidelines available online which have thoughtful discussion regarding Indigenous engagement, Continuous culture and ongoing responsibilities,

I had great hopes for Musee Quai Branly in Paris, but in spite of Architect Jean Nouvel’s original concept for the museum, the more I read about it, the less convinced I am that the museum hits the mark for the people that it was supposed to champion. One of the most interesting articles that I’ve read is written by Alexandra Sauvage in reCollections, Vol 2,Number 2 called Narratives of colonisation: The Musée du quai Branly in context. Sauvage points out that:

“Whereas museums tend more and more to collaborate with Indigenous peoples in the preservation of collections and the development of exhibitions, the Musée du quai Branly proposes a complicated, marginalising and (most) un-traditional way for Indigenous communities to benefit from their cultural heritage. Clearly, everything indicates that it was a political choice to ignore the 30-year-long fruitful dialogue between anthropologists, curators and Indigenous peoples that has taken place worldwide, a dialogue ‘between cultures’ that has informed museum policies for the last decades. Instead of following this general path, the efforts of the MQB are directed to promoting the ‘aesthetics’ of the collections.”

On a more positive note, The Indigenous Repatriation Program has so far led to the return of more than 1,480 Indigenous Australian ancestral remains, with more than 1,200 coming from the UK. In 2019, the ancestral remains of 37 Aboriginal people were returned to Australia from London’s Natural History Museum. Narungga community representatives were part of a delegation receiving the remains of an ancestor who will be cared for at the South Australian Museum until the community is ready to conduct a reburial ceremony. The Museum will also look after another seven repatriated ancestral remains. The remaining 29 ancestral remains will go to the National Museum of Australia until the Ngarrindjeri, Far West Coast, Kaurna and Flinders Ranges communities are ready to lay them to rest.

Sacred Indigenous artefacts have been returned to traditional owners in Central Australia after spending almost a century in United States museums. The objects were displayed in Illinois after being taken in the 1920s. Due to their nature, the items cannot be revealed or seen by the public for cultural reasons. Elders spent months liaising for the return of 42 Aranda and Bardi Jawi objects, which arrived in Sydney from the Illinois State Museum.

The items were the first of many to be returned as part of a project that coincides with this year’s 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s first voyage to Australia. Project leader Christopher Simpson, from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), said the goal was returning items to country, not putting them on the shelf of another museum.

In The American Museum Of Natural History , New York City, Australia is represented within The Margaret Mead Hall Of Pacific Peoples. The museum has more than 25,000 ethnographic objects from the Pacific in its online database. Of these, 3,400 have originated from Indigenous Australian communities.

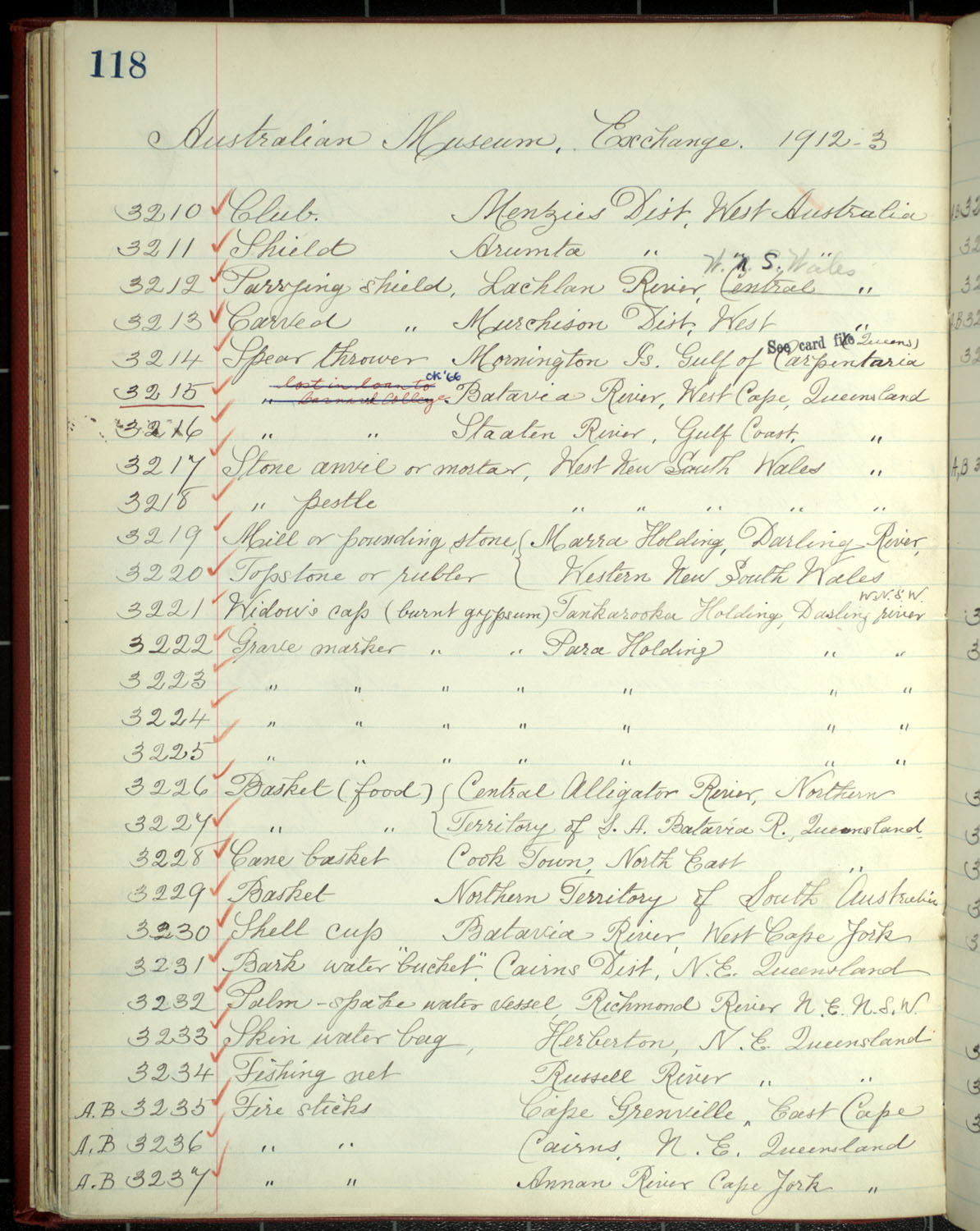

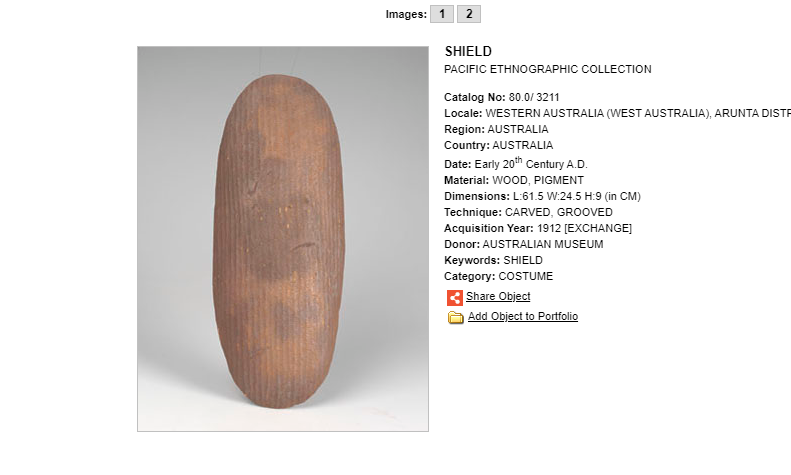

I was surprised to cross reference the objects with the registration catalogue to see who had donated the objects and the year that they had been donated – many items donated in the early 1900s. There was often a lack of useful information recorded and provenance was even more surprising. Objects had been exchanged from other museums including The Australian Museum, Museum of Florence, etc. as well as from private donors, often anthropologists and archaeologists who had worked in Australia with Indigenous communities.

There are still many contentious items in museums all over the world. I am not an Indigenous Australian, but I am a museum professional who sees no sense in objects which belong to living cultures being placed in storage or incorrectly displayed when they have significance and a part to play in modern day Aboriginal Australian cultural practice and heritage. How do we, as professionals, continue to raise awareness in cultural institutions around the world about the significance of these objects which need further research and evaluation?

Useful references:

<>

Practice note: The Burra Charter and Indigenous Cultural Heritage Management. https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/Practice-Note_The-Burra-Charter-and-Indigenous-Cultural-Heritage-Management.pdf

Narratives of Colonisation:The Musée du quai Branly in context. https://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_2_no2/papers/narratives_of_colonisation

Under Western Eyes’: a short analysis of the reception of Aboriginal art in France through the press. https://journals.openedition.org/actesbranly/581?lang=en

The Creation of Indigenous Collections in Melbourne: How Kenneth Clark, Charles Mountford, and Leonhard Adam Interrogated Australian Indigeneity https://journals.openedition.org/actesbranly/332?lang=en

Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council Annual Report (2018 – 2019). https://www.aboriginalheritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/victorian-aboriginal-heritage-council-annual-report-2018-2019

Indigenous People and Museums. https://nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/_lib/pdf/Understanding-Museums_Indigenous_people_and_museums.pdf

Continuous Cultures, Ongoing Responsibilities. https://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/3296/ccor_final_feb_05.pdf

Reuniting Indigenous ‘sticks’ with their stories: the museum on a mission to give back . https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/mar/04/reuniting-indigenous-sticks-with-their-stories-the-museum-on-a-mission-to-give-back

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (1999). The educational role of the museum. London: Routledge.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-07/indigenous-artefact-repatriation-nt/11677810