I have been taking pictures since I received my first Kodak instamatic camera at age 13. I’m not really interested in post editing images – I aim to photograph what I see with the naked eye – the subject, the light and the emotion that goes with capturing an image at a single point in time. Perhaps that is why I connected so strongly to the photographs and digital images at the Gulgong Holtermann Museum – a permanent exhibition showing part of the Holtermann Collection relating to Gulgong, NSW and which documents 19th century Australian life in the goldfields.

Behind the heritage walls, the museum’s contemporary exhibition space is engaging and entertaining for all ages. The text panels and interpretation are well done and further enhanced by wonderfully knowledgeable guides. The touchscreens and mounted photographs enable visitors to become completely immersed in the restored and digitised black and white prints from the collection.

Thematically as the visitor moves through the building, they can see the town and its people in 1872, learn the story of the men responsible for the images, and can find out more about the wet plate photographic techniques that they employed, the photographic equipment that was used, and the ‘discovery of the collection’ in 1951. There is also a comprehensive display of cameras from the earliest box and bellow-types up to the present and a film showing the restoration of the heritage buildings.

I came across the museum by accident while researching a member of the family who was an “ironmonger, oil and colourman” and had a shop in Herbert Street, Gulgong. I believe that it is one of the best small museums that I’ve visited world wide. There’s a great story behind its creation, because without a driven and committed Gulgong Community that fundraised over a million dollars to save two of its heritage buildings and a sleuthing Photographic magazine editor who asked the right questions to the State Library of NSW, the Gulgong Holtermann Museum may never have been born.

The images are amazing, but the fact that the glass plates used to make the images have survived at all, is a story in itself. Keast Burke was Editor of the Australian Photo Review when he enquired to the Mitchell Library in NSW about the existence of some glass plates associated with Bernard Holtermann. These particular plates showed panoramic views of Sydney in the 19th century. As a result, in 1951, 3500 or more glass plates (including the Gulgong plates) were unearthed from a garden shed in Chatswood, NSW. The glass plate negatives were donated to the Mitchell Library in 1952 by Holtermann’s grandson and became known as the Holtermann Collection.

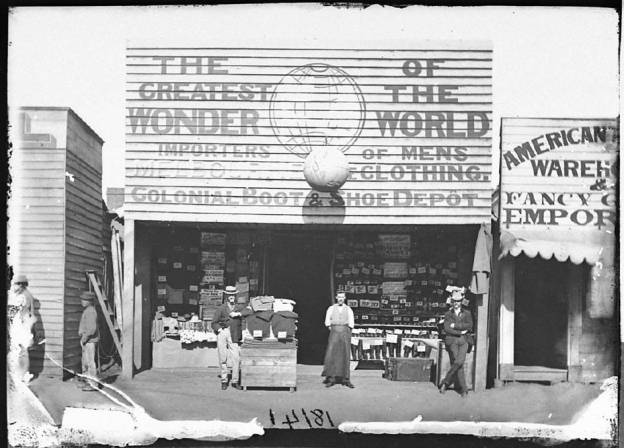

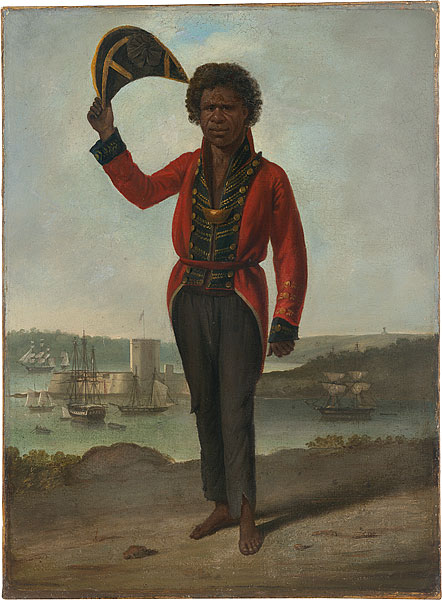

Merlin and Bayliss photographed literally everything in the rapidly growing towns of Gulgong and its surrounding villages – including diggings, businesses, the buildings, street scenes, panoramic views and the local people.The images were distinctive because of the groups that they photographed casually standing in front of the buildings – owners, workers and passers by – providing a microscopic view of life in a classic Australian gold rush town.

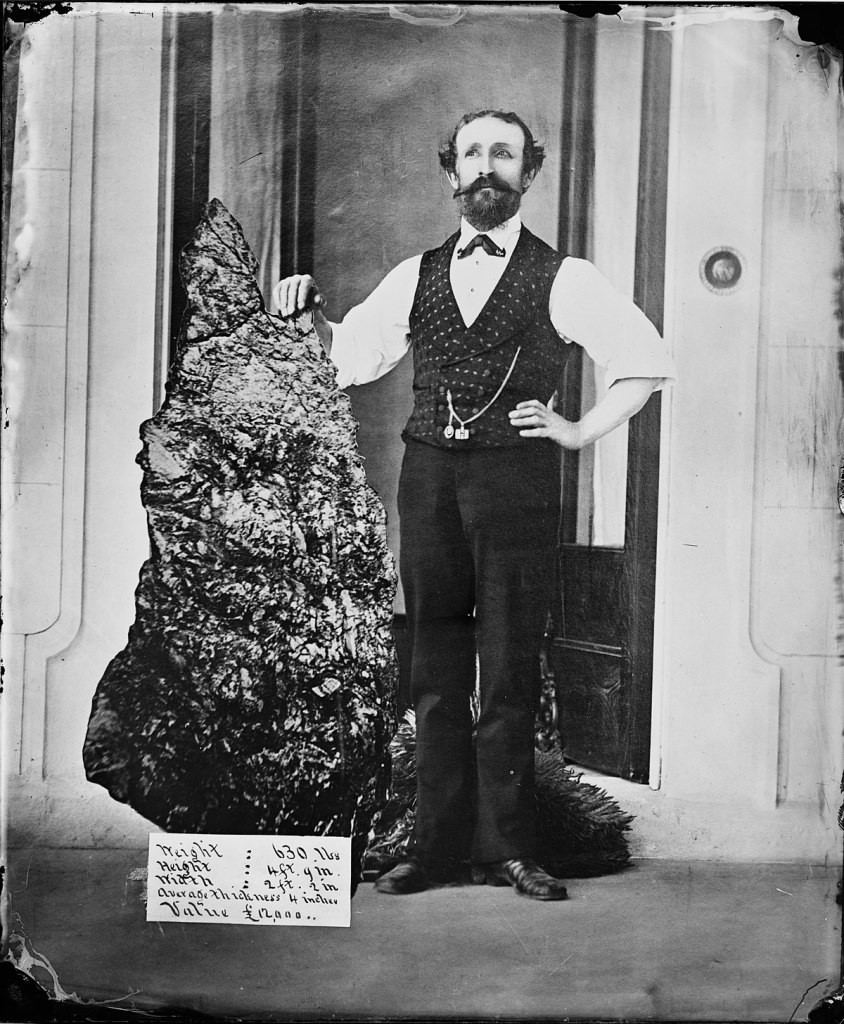

Quite apart from the technical expertise required by Merlin and Bayliss for such a massive undertaking, it is their haunting images which capture the essence of each subject so beautifully and engage with the visitors to the museum. They bring Gulgong to life and create a real sense of the way that people survived in the goldfields at that time. Even in the harsh winter environment of 1872, the subjects are captured in their finest clothing, photographed with their prized possessions or in front of their shops or outside basic dwellings which were constructed from locally found materials. The photographer needed the subjects to be still for 8 seconds and so you can observe that many of the children have their heads held by a grownup or ghostly animals and people appear in the frame because unfortunately there was movement during that 8 seconds. The Holtermann collection is deemed so important that it was included on the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World register in May 2013.

Thanks to the support of the State Library of NSW and a range of sponsors, the Gulgong Holtermann Museum is the only detailed and permanent exhibition of the unique Holtermann collection. It is a contemporary museum housed in two beautifully restored 1870’s gold rush buildings situated in Mayne Street, Gulgong. These two buildings along with many others were photographed in 1872 by Merlin and Bayliss and later acquired by Holtermann to form part of the UNESCO listed Holtermann Collection of photographs. So much of the town is still recognisable today from the digital collection and it’s an added bonus to stare into the faces of the people who lived in Gulgong in the 1870s and experience both evocative and humbling.

Bernhard Otto Holtermann was a man of many talents, but for me, his most important role was that of wealthy gold miner and philanthropist who commissioned travelling photographer Henry Beaufoy Merlin, ((founder of the American and Australasian Photographic Company (A & A Photographic Company)) to photograph a massive piece of reef gold found in his mine before it was sent to be crushed. This meeting led to an amazing photographic partnership, Holtermann offering land for Merlin’s studio in Hill End and then sponsoring the work of Merlin and his young assistant, Charles Bayliss to photograph Hill End and Gulgong. Holtermann, a German migrant, supported Merlin’s quest to document the settled areas of New South Wales and Victoria and wanted to present these photographs of Australia overseas as part of an International Travelling Exposition to advertise the colonies and encourage migration.

After Merlin’s death in 1873, the project was continued by his assistant, Charles Bayliss and the collection, amounting to around five hundred glass plate negatives, was purchased by Holtermann to add to his own collection of previously commissioned works by Merlin and Bayliss. Only a small percentage of the A&A Photographic Company’s output has survived, but 3,500* small format wet plate negatives (including extensive coverage of the towns of Hill End and Gulgong) and the world’s largest wet plate negatives, measuring a massive 0.97 x 1.60 metres, are held by the State Library of New South Wales.

You can see more of Merlin and Bayliss’s work just over an hour away at the Hill End historic site which is managed by National Parks NSW. The Heritage Centre is located in the restored 1950’s Rural Fire Service Shed and also displays images from the Holtermann collection showcasing the Hillend goldfields. It adds value to your site visit making it easy to reimagine the scenes outside from Merlin and Bayliss’s images in your head.

*Merlin retired as manager of the NSW branch of A&A Photographic Company in February 1872 and sold the business to Andrew Carlisle. Unfortunately, Carlisle sold all the view negatives of the company in September 1872, so it seems all the views taken throughout Victoria and NSW by Merlin and Bayliss in 1870 and 1871 were destroyed at that time. Some reports of 17,000 images.

Extra notes

In 1875, Holtermann and Bayliss produced the Holtermann panorama – a series about Sydney taken from the tower of his home in North Sydney, which was an impressive 10 metres in length and received the Bronze award at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 and a Silver Medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle Internationale in 1878.

The advertising below states that Beaufoy Merlin also created 800 views of Parramatta but sadly this collection does not appear to be intact. There are some of his images in the Sydney Living Museums and Historic Houses Trust Collections, J.K.S. Houison collection held by the Society of Australian Genealogists. Anyone with glass plate negatives in their shed, please come forward now.

Excerpt from Sydney Morning Herald, 21 September 1870 – Advertising

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13219139

Further Reading

Creating with Communities/Make Museums Matter/The Museum of the Future https://themuseumofthefuture.com/2017/12/19/creating-with-communities-make-museums-matter/

Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museums/The Museum of the Future https://themuseumofthefuture.com/2019/05/15/intangible-cultural-heritage-and-museums/

Perspectives on Digital Engagement with Culture and Heritage by Jasper Visser in Inspired by Coffee https://inspiredbycoffee.com/ibc15par/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Visser-Summer131.pdf

Museums of the Future – Selected Blogposts about Museums in times of technological and social change. Jasper Visser https://themuseumofthefuture.com/download/1594/

Active Participation: Museums Empowering the Community by Marilyn Scott on Museum-id https://museum-id.com/active-participation-museums-empowering-community-marilyn-scott/

https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/henry-beaufoy-merlin-australian-showman-and-photographer

https://geoffbarker.wordpress.com/2018/11/25/beaufoy-merlin-showman-and-photographer/

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1PbGMMCa5nGlHphpsVhX9EoiIb4IHbwp9/view

A modern vision – Charles Bayliss Photographer, 1850 -1897 https://www.nla.gov.au/pub/ebooks/pdf/A%20Modern%20Vision.pdf