I used to be an Australian, but now I’m not so sure. Who knew that a virus called Covid-19 would be enough to tip state and territory leaders over the edge, taking Australia back 120 years to a colonial mindset? I’m thinking back to a time when I did some work in Canberra before our lives were changed so dramatically by a pandemic.

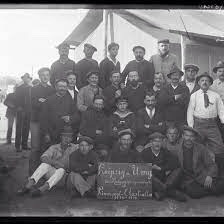

In early 2019, The National Archives of Australia (NAA) had an exhibition about the Australian Constitution and the Federation of Australia at the Museum of Australian Democracy in Canberra while renovations were being carried out on their own building located nearby.

It was interesting to survey visitors to the exhibition and ask them some questions about our Constitution. (Anecdotally I’d say that other than law students or political scientists that most people passing through the exhibition had not spent time dissecting the document in question.) The NAA wanted to understand – whether visitors to the exhibition had actually read the Australian Constitution; what they knew about the creation of the Constitution; what they knew about the Federation of the colonies/territories and whether or not they thought that the Constitution needed to be changed in some way. If they did think that the Australian Constitution should be changed moving forward – they were asked how it should be changed and why? Imagine carrying out this survey in the different states (particularly WA and QLD) and territories right now in 2021 to see how people’s views have changed over the past 18 months.

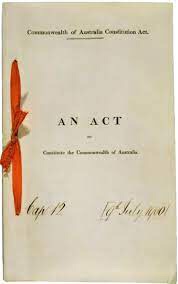

Surprisingly, it took 10 long years to draft the Constitution before it was given Royal assent by Queen Victoria (Queen of the United Kingdom) in 1900. The passing of the Constitution enabled Australia’s 6 British colonies to become one nation – the Commonwealth of Australia, on 1st January, 1901 – twenty one days before the death of the Queen.

Western Australia was the last colony to decide whether or not it would accept Federation. Strangely, in the early 1890s, New Zealand had considered becoming part of Federated Australia ahead of Western Australia’s decision but the fact that the Maori had the Treaty of Waitangi in place (and our Indigenous Australians were not similarly recognised) and the difficulty of protecting two island nations from a military perspective proved to be too much of an issue in the end.

The other colonies had each held special votes or referendums in 1898 and 1899 – and in all of them the majority of voters said ‘yes’ to the Constitution Bill, accepting the new Australian Constitution. Western Australia had only just become a self-governing colony in 1890 and did not have its referendum until the end of July 1900. By then, Australia’s Constitution had Britain’s parliamentary and royal approval and arrangements for the new federal system were already in place.

Under the new Constitution, the former colonies (now called states) would retain their own systems of government, but a separate, federal government would be responsible for matters concerning the nation as a whole. For the most part, this system works, but also there could be benefits to having a consistent national approach to areas such as health and education and the management of utilities such as gas and electricity.

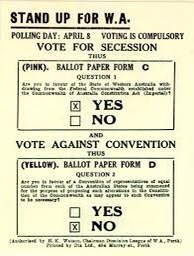

Historically, secession has been discussed in Western Australia on more than one occasion. It has been a serious political issue for the State, including a successful but unimplemented 1933 State referendum. The Constitution of Australia Act, however, describes the union as “one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth” and makes no provision for states to secede from the union.

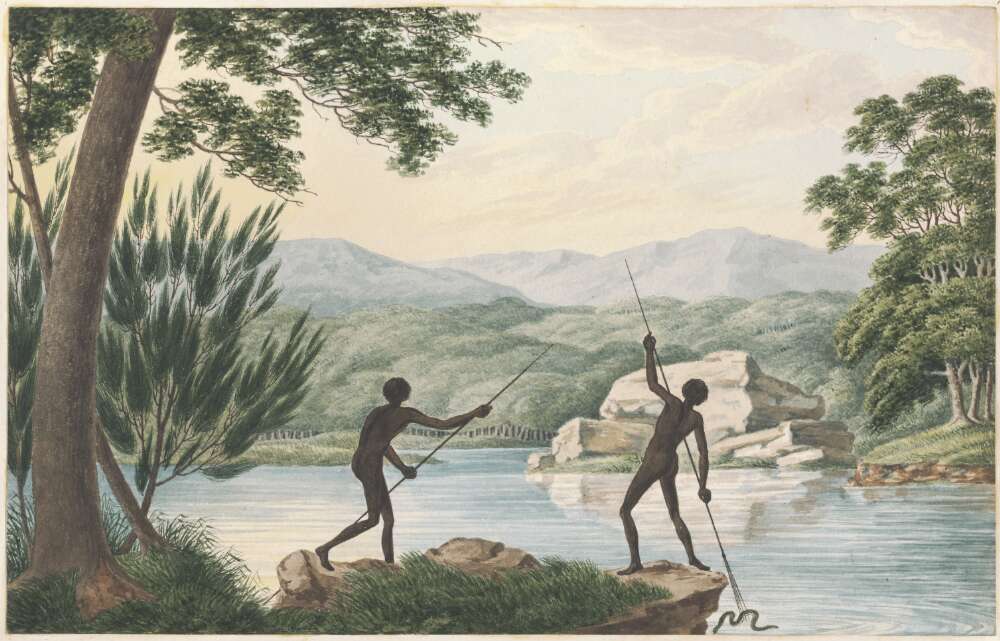

Federation in 1901 was no cause for celebration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who after 60,000 years were dispossessed of their land and forcibly removed from country onto missions and reserves. The only recognition of First Australians in the new Constitution was discriminatory. Federal laws could not be made for them, they were not counted in the census and most could not vote (although Indigenous Australians in South Australia had the vote pre-Federation in the 1890s). Sadly, the authors of the Constitution believed that Indigenous Australians would die out and so didn’t require recognition or special laws.

The process to change the Constitution is very different from the way other laws are changed. The Federal Parliament may pass a law proposing changes to the Constitution, but a change will only be made if it is approved by the people through a referendum. From the National Australian Archives resources:

The power of the Australian people to make change to the constitution is given to them by Section 128, ‘Mode of altering the Constitution’: ‘… a proposed law is submitted to the electors [and] the vote shall be taken in such a manner as the Parliament prescribes’.

For a referendum to be successful and the alteration to the constitution to be passed, a double majority vote must be achieved, which is:

- a majority of voters in a majority of states (at least four of the six states)

- a national majority of voters (an overall YES vote of more than 50 percent).

If the double majority is achieved and the proposed alteration to the constitution is approved, ‘it shall be presented to the Governor-General for the Queen’s assent’ (Section 128).

The 1967 referendum – in which over 90% of voters agreed that First Australians deserved equal constitutional rights – remains the most successful referendum in Australian history. But this achievement, framed by campaigners at the time as ‘equal rights for Aborigines’, did not occur in isolation or without a long history of agitation, action and appeal.

The decades following 1949 brought about several changes to the Constitution Act. According to Helen Irving, (Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series. 2001) “In 1967, changes gave the Commonwealth the power to make special laws for the Aboriginal people. Australia’s formal constitutional and legal ties with Britain were severed. The White Australia policy was ended, and multiculturalism was introduced. Australia increasingly looked to, and invoked, its international obligations in passing and upholding Commonwealth laws. The notion of citizenship began to stretch beyond Australia’s nationalist concerns, to a wider, international set of values.”

I’ve often wondered if some of the attitudes that Australians held arose because before 1949 Australians held the status of being British subjects. This remained true until the enactment of the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 which came into effect on the 26th January, 1949. Did this sway people to think as if they were British first rather than Australian? I know that many older Australians referred to England as “home” even when they were born in Australia. The legacy of British Imperialism had seeped into the minds of many Australians and “white-washed” their views on historical events and attitudes to Indigenous Australians and newly arrived migrants from non-British counties. It is not surprising that non-English speaking European migrants new to Australia also kept their country of origin allegiances for the first and second generations before they became “Australian”. Migrant families like my own suffered Australia Wartime internment during WWI and WWII based on family name and occupation even though they had arrived as indentured migrants from Germany in the 1850s. These people were not always overseas residents but were naturalised citizens and even born in Australia.

Realistically, most of us are migrants to this country. We have all brought with us bits of the cultural heritage that we came from to add to a growing population – making rich and diverse communities Australia wide. I hope that moving forward we are strengthened by the community values which can’t be broken by a pandemic. Australia made it through the Spanish Flu and can do the same now, remembering how we have joined together to form a single nation – Australia.

Strangely enough there are quite a few parallels with the pandemic today and the Spanish Flu more than 100 years ago. You get a sense of déjà vu reading about the border closures, quarantining, development of a flu vaccine by CSL, blame gaming between the states and last but not least that the Spanish Flu reached WA much later than the other states.

“In Australia, while the estimated death toll of 15,000 people from Spanish Flu was still high, it was less than a quarter of the country’s 62,000 death toll from the First World War. Australia’s death rate of 2.7 per 1000 of population was one of the lowest recorded of any country during the pandemic. Nevertheless, up to 40 per cent of the population were infected, and some Aboriginal communities recorded a mortality rate of 50 per cent.”

I hope that at the end of this Covid -19 pandemic I will still be an Australian and not a person defined by my State, Local Government Area or my vaccination status. I will look forward to seeing what the National Museum of Australia records on its online Bridging the Distance Facebook page after the success of Momentous – an audience driven participatory evolving record of recent events in Australian history compiled after the devastating 2019/2020 bushfire season.

Extra reading

https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/influenza-pandemic

https://www.aph.gov.au/binaries/senate/pubs/pops/pop37/irving.pdf