In Part two of this post, I’d like to think more about the “decolonisation” of cultural institutions and how this could impact on Australia and the way it is viewed by visitors overseas. Do cultural institutions present Australian history and cultural heritage to reflect our ever evolving nation post British colonisation and including those who have migrated to Australia up to the present day?

I would say that our Colonial past has synergy with other parts of the world colonised by the British – such as the United States, India, Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong. British Colonial Governors were regularly transferred to different parts of the British Empire and used convict labour to put their stamp onto the newly formed colonies. This period of history provides the earliest evidence of Australia’s changing cultural heritage post British settlement. After losing its American colonies in 1783, the British formed six colonies in Australia. They began to create a European-style “built environment” including townships, infrastructure and industries, large scale farming and trading between colonies and with other nations.

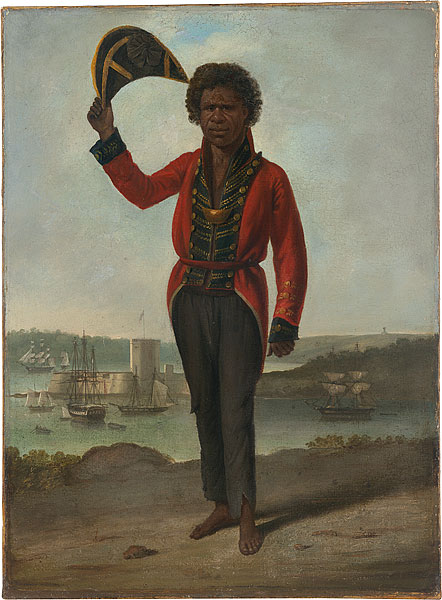

Calla Wahlquist from The Guardian wrote an article “History is Messy” about the National Galleries Victoria’s (NGV) concurrent shows called Colony (1770-1861) and Colony (Frontiers), exploring Australia’s complex colonial past and the art that emerged during and in response to this period. Presented concurrently, the two exhibitions offered parallel experiences of the settlement of Australia. Drawing from public and private collections across the country, Colony: Australia 1770–1861, brought together the most important examples of art and design produced during this period and surveyed the key settlements and development of life and culture in the colonies. Importantly, the exhibition acknowledged the impact of European settlement on Indigenous communities. Such an exhibition would have relevance in the UK and other Pacific nations that similarly were impacted by British explorers and colonists.

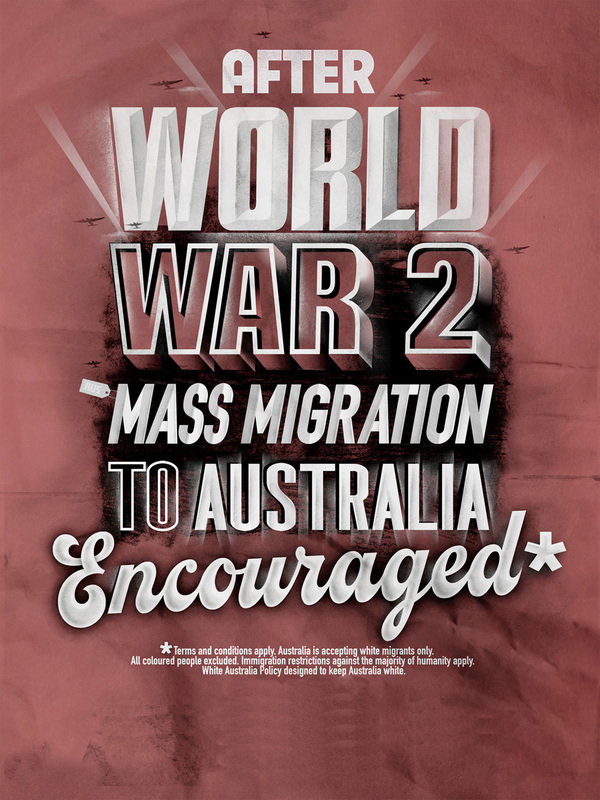

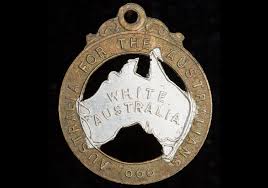

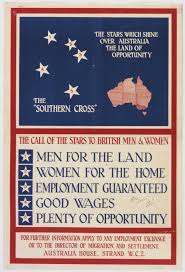

When the six colonies in Australia federated in 1901 and the Commonwealth of Australia was formed as part of the British Empire, there was widespread public support for the adoption of a national immigration policy and administration post Federation. Immigration was at the time administered separately by the states. All of the major parties involved in the new Federal Parliament held policies deliberately aimed at the exclusion of non-European migrants. The Immigration Restriction Act 1901, included a ‘dictation test’ for those seeking to immigrate that could be given in any European language, and was the beginning of what became known as the ‘White Australia Policy’. This policy remained virtually unchanged until after the Second World War.

Until 1949, Britain and Australia shared a common nationality code. The Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 created an Australian citizenship and the conditions by which it could be acquired. An Australian citizen was also considered to be a British subject.The Australian Citizenship Amendment Act 1984 was aimed at removing discriminatory aspects of the Act in relation to sex, marital status and nationality. The English language requirement was changed from ‘adequate’ to ‘basic’ and applicants over 50 were exempted from the English language requirement. Of particular importance, the definition of the status of British subject was repealed in order for the Act to reflect the national identity of all Australians. By the end of the 1980s, the total number of migrants from Asia overtook the total number from the UK.

250 years after James Cook’s arrival, what are we doing to ensure the quality control of this information about Australia’s history on the world stage? There is a great deal of chatter worldwide about whether or not cultural institutions and their collections can be “decolonised”.

“To decolonise is to add context that has been deliberately ignored and stripped away over generations. There are many examples of the misrepresentation of objects in museum displays that have only been corrected after dialogue with source communities. And there are countless instances where interpretation still needs to be rectified and stories freshly told.” (Sharon Heal – 2019 Policy article – UK Museums Association)

I think that it’s about more than that. It’s about being honest, stripping back the imbalance of power that occurred in the past (often unknowingly), really looking at inadvertent racism or examining the way that we tread “softly, softly” on difficult subjects like “The Stolen Generation”, “Slavery in Australia” or the “White Australia Policy”. It’s about looking carefully at museum collections – empowering them by reinterpreting and researching them, perhaps even repatriating objects with significance to living cultures or changing direction to be more “inclusive”. It is critical to consider the present diversity of museum audiences when evaluating objects in specific collections – are they relevant for each museum’s vision for the future or are they stuck with interpretation that belonged to times past, older exhibitions and a different type of museum visitor.

White Australia Poster

White Australia Migration Weekly 1945

NMA collection

NMA collection

NMA collection

Museums must be safe places for inter-generational learning and education, spaces for healing and reflection and a place where everyone feels welcome and the majority of visitors would want to return again and again. In the era of Covid-19 when cultural institutions are about to take a huge financial hit – getting your house in order is the best way to stay relevant when the doors to your institution reopen.

The Washington Post defines decolonisation as “a process that institutions undergo to expand the perspectives they portray beyond those of the dominant cultural group, particularly white colonisers.”

There are several ways to promote Australia in cultural institutions overseas. The first and simplest method is to design travelling exhibitions in partnership with museums that may have objects in their collections which would enhance an existing exhibition or has had a direct connection which might be relevant to the subject matter in the exhibition.

Australia is very much a nation of migrants from 1788 until the present day. We have a number of good “Migration” museums and museums reflecting the migrant contribution to Australian culture around the country. Specific collections relating to our migrant history can be found at the Migration museums in Melbourne, Adelaide, and sections of the Australian National Maritime Museum (Sydney), National Museum of Australia (Canberra), National Archives of Australia (Canberra). There are also “specialist” museums such as Sydney Jewish Museum, Jewish Museum of Australia (Melbourne), Jewish Holocaust Centre (Melbourne) and “multicultural” museums e.g. Multicultural Museums Victoria (MMV) an alliance which is an Australian first including the Chinese Museum, Co.As.It Italian Historical Society & Museo Italiano, Hellenic Museum, Islamic Museum of Australia and the Jewish Museum of Australia. I doubt that many of these museums would have an opportunity to exhibit travelling exhibitions overseas which is a pity because I’m not certain how we are seen as Australians from a global perspective.

I’ve seen some sad misrepresentation of Australia in world class museums, but in direct contrast, I’ve been very proud to see one of our difficult stories connecting with audiences in the UK. I was lucky to visit “On Their Own – Britain’s Child Migrants”, a collaboration between the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney and National Museums Liverpool in both Sydney and Liverpool, UK and observe the emotional audience response to the telling of this story from our difficult past.

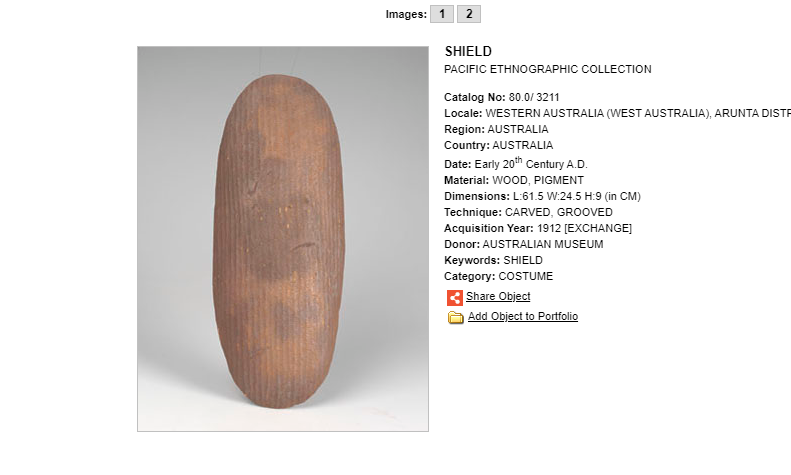

Sometimes the absence of objects in museums overseas also tells a story about how Australia is seen on the world stage. If you look into the online collections and exhibition databases of major cultural institutions overseas, Australia is either not mentioned, poorly represented across layers of history and cultural diversity or aspects of the Australian collection have been vaguely researched or mislabeled or tagged as Australian when they are not, or the provenance is weak to say the least (see Part one of the post). This is an opportunity for Australian cultural institutions to support or partner with museums overseas to assist with researching collections or reinterpreting out of date displays.

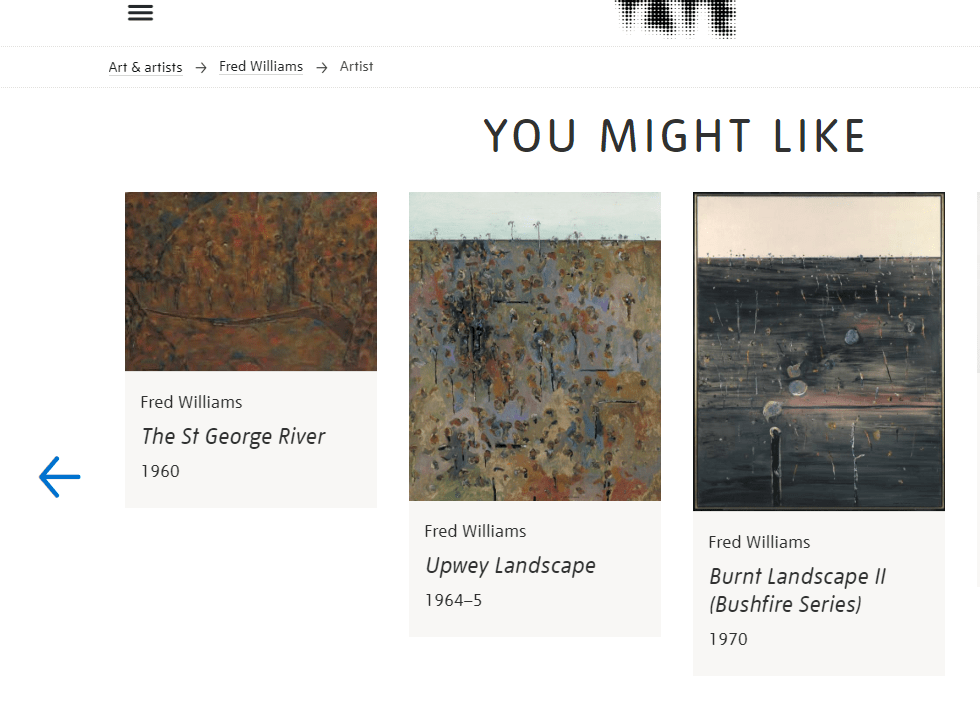

For example, I have seen wonderful exhibitions of Fred William’s work in Australian galleries over many years and would love to have seen some of those beautifully curated exhibitions travel the world. The works would also lend themselves to digital or immersive experiences of the outback Australia. Of course Williams is only one of hundreds of 19th and 20th century Australian artists who would look good on the walls of cultural institutions in other parts of the world.

Williams (b.1927) is one of my favourite Australian artists because his works are truly evocative of the Australian landscape. Fred is the first and only Australian artist to have exhibited at MoMA (New York) and this happened in 1977- 43 years ago. Sadly there are few other references to Australian Art in the MoMA collection. The artists represented in the collection are – Leonard French b.1928, Tracey Moffat b.1960, Toba Khedori, b.1964, Sydney Nolan b.1917, Anton Bruehl b.1900 (born in Australia), Shaun Gladwell b.1972, and the University of Western Australia for their Pig Wings Project 2000-2001.

In the UK the Tate Gallery holds 30 of Fred Williams works and works by over 70 Australian artists including those with Indigenous and Multicultural cultural heritage.

I was excited to find 619 references to Australia in the online collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York but so many of these works were by Australian born artists who were more American or British in reality. Indigenous Australia seemed to be well represented in the online collection, but actually looking at these objects and artworks reveals that a large proportion are actually African, Indian, European, Fijian, South East Asian or from Papua New Guinea and New Zealand.

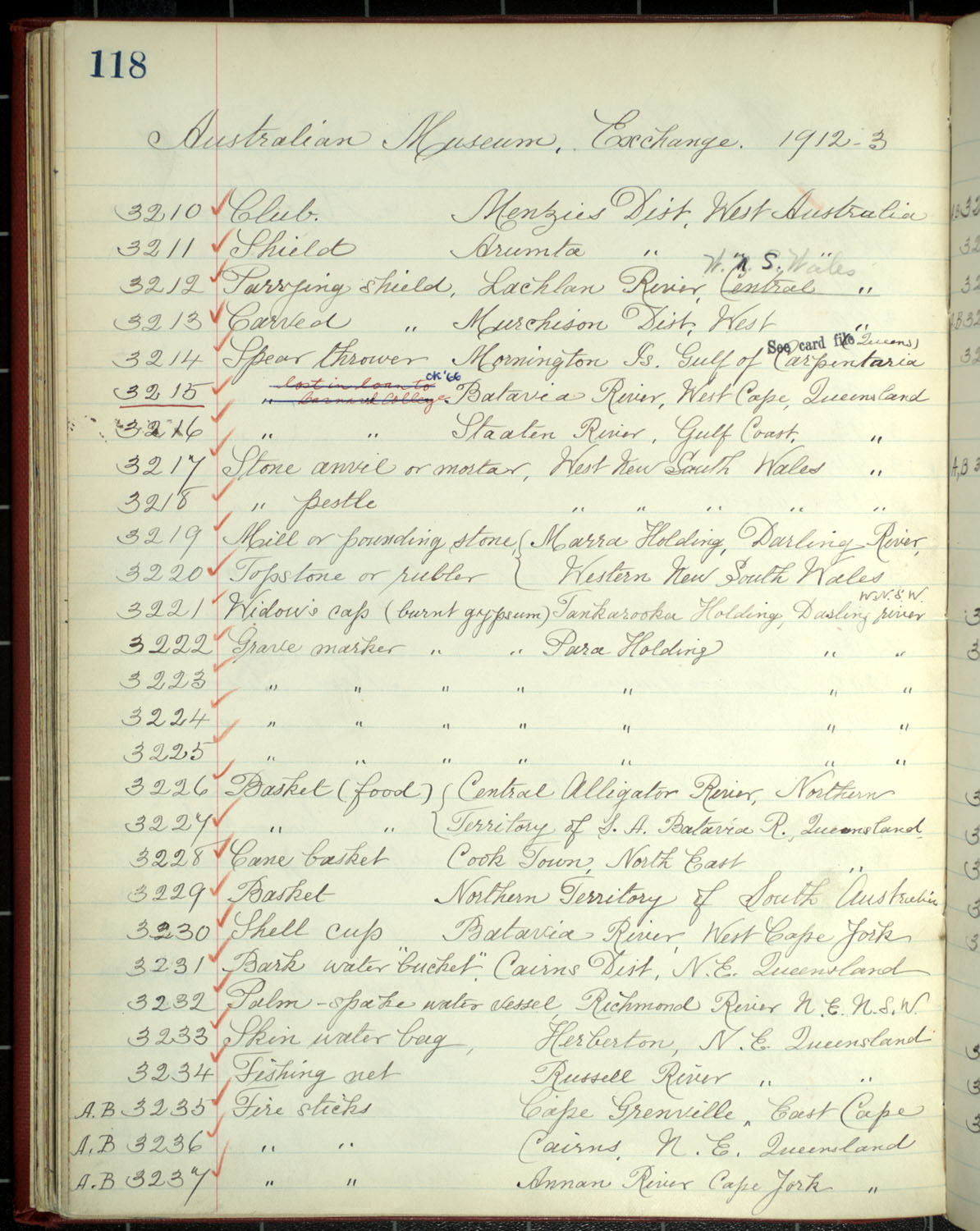

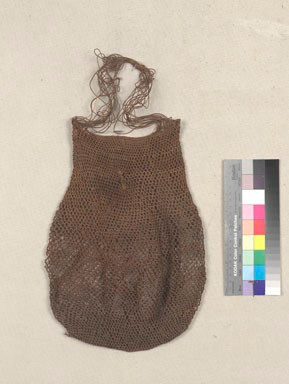

In the British Museum collection online there are over 7,000 references to Australia but closer examination reveals that hundreds of these are objects from other countries which had been on loan to Australian Museums for exhibitions rather than actually being sourced from Australia. Thousands of objects are Indigenous Australian pieces – tools, weapons, bags, adornments, artwork, shields etc. There are more recent art works and decorative objects, coins and banknotes and photographs and colonial paintings and engravings but only one record for Multicultural Australia – Ithaca I; print; Aida Tomescu (Print made by); 1997 .

Australia’s Multicultural heritage is unique and an interesting part of the fabric of our nation and there are many stories in museums in Australia that could be shared world over. In 2011 Viv Szekeres wrote an article ‘Museums and multiculturalism: too vague to understand, too important to ignore’ . To reflect our changing cultural heritage may require a rethink in collection practices – a more strategic collection practice in partnership with different communities.

The National Galleries Victoria presented a major exhibition of influential British artist, David Hockney, in 2016 at NGV International. The exhibition, curated by the NGV in collaboration with David Hockney and his studio, featured more than 700 works from the past decade of the artist’s career – some new and many never-before-seen in Australia – including paintings, digital drawings, photography and video works. We seem to do really well collaborating with overseas museums to highlight their collections but what about the reverse situation to highlight our Australian collections overseas?

Useful references

What does it mean to decolonize a museum?

Who’s afraid of decolonisation?

The ‘decolonization’ of the American museum – The

Australia’s hidden history of slavery: the government divides to conquer

Understanding Museums – Museums and multiculturalism

Museums Association UK Collections 2030 DISCUSSION PAPER